Joe Biden’s fist-bumping visit to Saudi crown prince Mohammed bin Salman was always a questionable exercise. Three months later, the US president’s reward has not been the hoped-for increase in oil output, but a headline cut of 2mn barrels a day by the Opec+ group that has allied the oil cartel with Russia since 2016. Five weeks before US midterm elections in which gasoline prices could play a decisive role, this looks like a snub. It also suggests Saudi Arabia is sticking fast to its relationship with Moscow, even as Vladimir Putin escalates his war in Ukraine. The kingdom may feel it is acting in its own and the cartel’s best interests, but its actions may prove a strategic error.

Saudi and Opec officials insist the cuts were not politically motivated. Faced with a likely recession in Europe and elsewhere that will depress demand, they say they are attempting to put a floor under prices, protect revenues and increase capacity. After falling by a quarter since June, global crude prices are, in equivalent terms, also well below the sky-high levels natural gas and coal have reached thanks to Russia’s war.

Yet the move to reduce production now is part of a broader struggle for control of the global oil market. Saudi Arabia has been irked by US-led attempts to influence prices. The Biden administration has pushed for price caps on Russian oil — to squeeze Moscow’s revenues — from the G7 big democracies and the EU. Opec sees this as an attempt to shift the balance of power towards consuming nations, and fears such a mechanism could one day be deployed against it.

The US has also engaged in the largest ever release from its Strategic Petroleum Reserve to try to tamp down crude prices, and gas prices at US pumps — an intervention as hefty as Opec’s new cuts. Releases have sometimes run at about 1mn b/d, roughly equivalent to what Opec’s cutbacks will amount to once the underproduction of some members compared to their quotas is factored in.

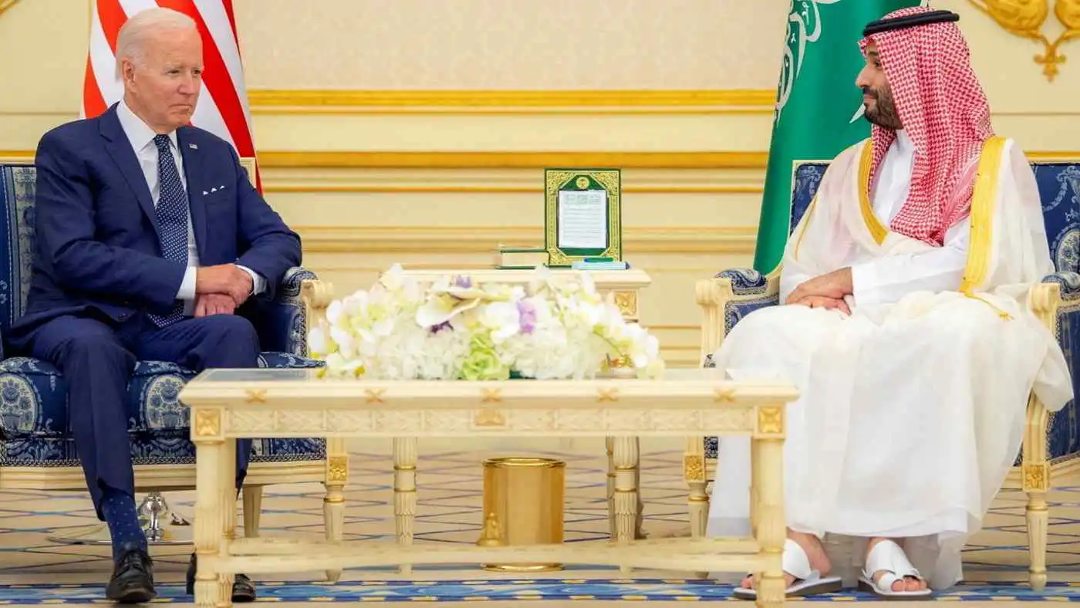

Image: US president Joe Biden visited Saudi crown prince Mohammed bin Salman in July this year © Bandar Algaloud/Saudi Royal Court/Reuters

The cartel is trying to regain control of the market and demonstrate that it still has the power to set the price. Saudi Arabia is surely engaged in political signalling, too, to a US president who called it a “pariah” after the brutal murder of the journalist Jamal Khashoggi, and an administration it feels is giving insufficient support to Riyadh’s security in the region. It aims to show it has other friends, in Beijing, New Delhi and Moscow.

The Saudi crown prince risks overplaying his hand, as he has often done in the past. China, India and Russia are unlikely to extend anything like the same security protection to Saudi Arabia that the US has done over several decades. Pushing up oil prices now may only deepen any impending recession and the resulting destruction of demand. An irate White House has hinted it may now release even more oil from America’s stockpile. US lawmakers are calling to revive so-called Nopec legislation, which aims to crack down on oil cartels.

The lesson for the US and western allies is that their partners in the Gulf are not reliable when it comes to energy, and Opec is determined to maximise revenues from an asset for which demand must eventually be slashed by western-led efforts to combat climate change. It sees no obligation in the meantime to provide energy security cheaply to its customers.

Western consumer nations have few short-term, supply-side, answers other than investing in further fossil fuel production that would run counter to their climate aims. The long-term answer to all the multiple energy and climate problems they now face is the same: to make real efforts, which have so far barely begun, to reduce oil demand — and to speed up the dash to sustainable, green sources.

Author: Financial Times